Papers in the JIIA Strategic Commentary Series are prepared mainly by JIIA research fellows to provide comments and policy-oriented analyses of significant international affairs issues in a readily comprehensible and timely manner.

Democracy and disinformation

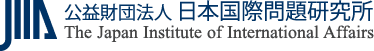

An open democratic society is one that allows its members to access information from both inside and outside the country presenting a diversity of viewpoints, to freely express their own thoughts, and to involve themselves in free and fair national governance. The role of the media has traditionally been emphasized with regard to accessing information. Traditional media play an important role in shaping public opinion and in providing information that enables members of the public to participate actively and effectively in a democratic society (see Figure 1). Freedom of the press1 as guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution of Japan is also one of the core values of democracy.

Figure 1: Agenda setting model

Source: Prepared by author based on Rogers and Dearing (1988)

However, democratic processes worldwide are now facing great challenges due to disinformation campaigns.

"Disinformation" refers to false or misleading information created to obtain political or economic benefits or deliberately deceive the masses. It hinders sound democracy because it can undermine public confidence in government and traditional media, impede citizens' ability to make decisions based on sufficient and accurate information and even encourage radical ideas and activities2. Disinformation does not include inadvertent misinformation, satire or parody, or clearly partisan news and comments3.

"Disinformation campaigns" are activities through which various domestic and foreign actors distort public opinion, create social or political instability or influence government policy-decision processes by spreading disinformation, and they can even have a serious impact on national security4. Disinformation campaigns by third countries are also a part of hybrid warfare5.

Why is "disinformation" garnering attention now?

In recent years, there have been a series of disinformation campaigns in Europe and the United States. In the US, fake news favoring Donald Trump was spread during the 2016 presidential election. In Europe, rumors during the 2017 French presidential election that Emmanuel Macron had established a shell company in a tax haven and suggestions that German Chancellor Angela Merkel had terrorist connections because of a photograph taken of the chancellor with a Syrian refugee after a 2016 terrorist attack by an immigrant were spread by various social media.

Such circumstances have triggered a growing sense of crisis in Europe at the level of general public opinion as well as at the government level. According to the European Commission, 83% of European citizens in 2019 considered fake news to be a threat to democracy, while 73% of Internet users were concerned about pre-election disinformation on the Internet6.

The existence and threat of disinformation have thus been recognized over the past several years primarily in Europe and the US, where this disinformation has often been termed "fake news". Today, however, the term "disinformation" is widely recognized around the world, and foreign disinformation attacks are seen as a serious threat to democracy. What are the main factors behind this? The following two factors should be noted in particular.

The first is the rapid progress and spread of information and communication technology. Not only has the amount of information accessible to the general public increased dramatically due to the popularization of the Internet, but the ways the general public is involved with information has also changed significantly due to the penetration of social and online media. New technology is being used to disseminate disinformation instantly and extensively with accurate targeting via social media. As has been pointed out, this has made social media an echo chamber for disinformation campaigns7.

The second factor is the pandemic. With the spread of novel coronavirus infections, a variety of disinformation about the virus has flooded Europe, the US and the rest of the world, and the threat of disinformation has become clearly acknowledged globally. During crises, people tend to become distrustful and anxious. This psychological state makes them more receptive to conspiracy theories and disinformation. Importantly, a flood of disinformation in such crises entails the risk of giving rise to social turmoil and impairing effective policy-making and public health activities.

The first and second factors interact with each other. Disinformation is a familiar threat that not only polarizes national public opinion but can also endanger the safety and health of citizens.

Examples of disinformation countermeasures from various countries/regions

Let us look at some examples of the disinformation countermeasures being taken in specific countries and regions. Europe has been actively implementing measures to combat disinformation for some time, and the EU is currently focusing on cooperation and collaboration among its member states as well as with NATO and other international organizations, private-sector groups, fact-checkers and experts.

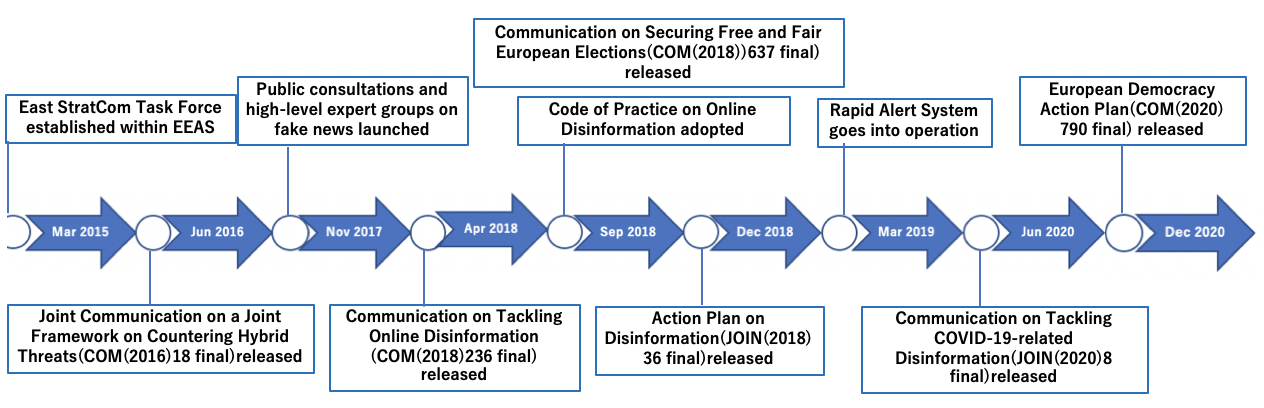

The EU's measures were originally aimed at responding to information warfare by Russia. Following the establishment of the East StratCom Task Force within the European External Action Service (EEAS) in 2015, communications on online platforms and hybrid warfare have been released since 2016, and 2017 saw the implementation of efforts that could be termed predecessors to disinformation countermeasures, including public consultations on fake news and the launch of a group of high-level experts. 2018 marked a turning point when the term "disinformation" began to be widely used in earnest. Communications were issued that pushed responses to disinformation to the forefront, and an action plan and code of practice8 on disinformation were subsequently released. In addition, a new European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO) staffed by fact-checkers, academics and researchers was established under the 2018 Action Plan, thus providing a structure to further strengthen cooperation with the EU and support for fact-checkers and researchers.

The response to disinformation underwent a drastic change in 2020. Criticism was leveled at China and Russia by name for spreading disinformation about the coronavirus during the pandemic. More potent measures were taken, including the announcement of a new action plan based on the recognition that disinformation threatens democracy (see Figure 2). There is also a move underway to newly regulate IT giants. On December 15, 2020, the European Commission announced two bills, the "Digital Markets Act" aimed at ensuring a fair competitive environment for business and the "Digital Services Act" focused on eliminating illegal content.

As of 2021, efforts are being pursued to reinforce the Code of Conduct announced in 2018.

Figure 2: Development of EU disinformation countermeasures

Source: Prepared by the author with reference to various communications released by the European Commission

Next, let us examine Taiwan's efforts to actively counter disinformation campaigns by China. The Taiwanese government took steps in preparation for Taiwan's January 2020 presidential election. In the 2018 Taiwanese local elections (commonly known as the nine-in-one elections) that served as a prelude to the Taiwanese presidential election, the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) suffered a serious defeat, and (still unsubstantiated) suspicions of Chinese interference hung over these elections.

To put to use the lessons learned from the nine-in-one local elections, the Taiwanese government adopted a three-pronged approach toward Taiwan's January 2020 presidential election - (1) a strategy for information dissemination by the government, (2) education and (3) legislation - aimed at curbing the social impact of false information originating in China. Summaries of these measures are given below.

| (1) | The ruling DPP set up teams in government ministries and agencies to monitor disinformation and respond promptly. When it was determined that certain information was likely to be politically impacted, attempts were made to disseminate information through online content such as press releases and short, clear and humorous Internet memes and to provide correct information immediately through press conferences by minister-level officials. | |

| (2) | Education was also bolstered. Efforts are being made to correct intergenerational disparities in the use of social media, including school education on media literacy and education for the elderly by non-profit organizations. | |

| (3) | On December 31, 2019, shortly before the January 11, 2020 presidential election, the DPP approved and passed an anti-infiltration act to prevent China from intervening in or interfering with the election. Individuals and groups donating to or supported by "hostile foreign forces" were to be punished by imprisonment of up to five years and fines of up to around $332,0009. |

Taiwan's policies have been cited by both domestic and international observers as successful examples of curbing disinformation from China.

Possible threats and current situations in Japan

The foreign policy, defense, society, public health and other dimensions of Japan's security could be adversely affected by influence operations and disinformation campaigns conducted by neighboring China or other countries, and prompt consideration must be given to this serious issue. Above all, China's aim is to reach out to public opinion in target countries to create an environment favorable to advancing its own policies. One of its objectives in Japan is to foster a positive view of China and, more strategically, to weaken the Japan-US alliance.

The reality, however, is that it is extremely difficult to prevent disinformation campaigns from overseas because there are few political or economic incentives10 and insufficient fact-checking functions to counter disinformation campaigns in Japan. In particular, Japan lags far behind internationally in fact-checking efforts that play an important role in dealing with disinformation during elections. According to the database of fact-checking websites compiled by the Duke Reporters' Lab at Duke University in the US, the three organizations accredited and registered as active fact-checking institutions in Japan accounted for only 0.98% of the 306 such institutions worldwide as of April 202111.

On the other hand, there are few disinformation campaigns being conducted in Japan from overseas, so Japan is not very vulnerable to their effects. The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake, and the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election all prompted the spread of false rumors, but these do not correspond to the disinformation campaigns discussed in this paper. Nearly all the misinformation running rampant during disasters arises domestically and is not deliberately spread for political or economic gain, while the possibility cannot be excluded that the misinformation generated by unidentified sources during the Okinawa gubernatorial campaign came from domestic opposition activists, given that the criticism therein was directed at a particular candidate (Denny Tamaki)12 and that it was spread in some instances by politicians and celebrities13. The large number of hot-button issues in Okinawa is one of its distinguishing features.

Various reasons can be cited for the relatively slight impact of disinformation campaigns and other influence operations in Japan conducted from overseas, especially from China. Some Western researchers have pointed out that Japan's society and organizations are more insular than those in the West14. There are also cultural and language barriers15. It has been noted that China's influence operations in Japan have had more limited success than in other democracies because many Japanese are skeptical of the influence of the United Front Work Department16. The impact is also believed by some to be dampened by the fact that communication between political elites and regular citizens via social media is less active than in other countries17.

However, disinformation campaigns by other countries, along with cyberattacks, are also means employed as part of hybrid warfare to win over public opinion in a target country or to disrupt its society at a stage prior to using force. For example, China is trying to deepen exchanges with Okinawan organizations that advocate independence for the Ryukyu people and to shape public opinion in ways advantageous to China; polarizing public opinion in Japan, alienating Japan from the US, and removing US forces stationed in Okinawa can be said to be important strategic objectives for China in achieving its national goals.

Issues Japan should address and the need for international cooperation

Authoritarian countries exploit the vulnerabilities of democracy, perhaps because the freedom of expression, the freedom of the press, and the democratic procedures that democracies value also provide opportunities for disinformation campaigns. A critical issue for Japan will thus be how quickly it can become more resilient to disinformation campaigns by other countries and minimize their impact on public opinion formation, the government's policy-making processes, and the health and security of its people.

This includes strengthening cross-ministerial efforts, as well as the government's strategy for disseminating information publicly, expanding fact-checking functions, collaborating with fact checkers, experts, and online platform companies, and continually analyzing public opinion and information. Education to cultivate the public's media literacy will also be important.

Meanwhile, international cooperation continues to see progress. The EU is currently seeking to build partnerships with other countries and regions to deal with concerns in maritime security, emerging technologies, cyberattacks, disinformation and other issues in the security and defense realms, and has expressed its willingness to actively cooperate with the Indo-Pacific region in combating disinformation18. European think tanks, too, are becoming more interested in Japan's measures to counter disinformation campaigns and engage in strategic communication.

In addition, new moves are underway in North America, including endeavors aimed at having Japanese experts participate in an international network organized to tackle disinformation and other issues pertaining to platform governance.

The extent of disinformation now puts it beyond the ability of any country to address on its own, necessitating cooperation between nations sharing the same democratic values and experience. With little experience and insufficient countermeasures, Japan has much to learn from other democracies confronting the same disinformation threat, and cooperation with other countries holds great potential for Japan as well.

*This is an English translation of the original Japanese version published on May 17, 2021.

1 Supreme Court Decision, November 26, 1969, Keishu 23-11-1490

2 European Commission, "Tackling Online Disinformation: A European Approach," COM (2018) 236 final, April 4, 2018, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0236&rid=2 (accessed April 20, 2021).

3 European Commission, "Action Plan against Disinformation," JOIN (2018) 36 final, December 5, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/eu-communication-disinformation-euco-05122018_en.pdf (accessed April 20, 2021).

4 Ibid.

5 Hybrid warfare is conflict in which state and non-state actors employ conventional and unconventional means to achieve a common political objective.

6 "Factsheet: Action Plan against Disinformation," European External Action Service, March 2019, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/disinformation_factsheet_march_2019_0.pdf (accessed April 20, 2021).

7 COM (2018) 236 final.

8 The Code of Conduct has been signed by Facebook, Google, Twitter and Mozilla and a roadmap for implementing the Code announced; Microsoft joined this group in 2019 and TikTok in 2020.

9 Linda Zhang, "How to Counter China's Disinformation Campaign in Taiwan," Military Review, September-October 2020; Aaron Huang, "Combatting and Defeating Chinese Propaganda and Disinformation: A Case Study of Taiwan's 2020 Elections," Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, July 2020.

10 Instituto Affari Internazionali, "EU-Japan Cooperation in Countering Disinformation Campaigns," On video, YouTube, April 15, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fvyG9yX0NUc&t=476s (accessed April 20, 2021).

11 "Fact-Checking," Duke Reporters' Lab, https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking/ (accessed April 20, 2021).

12 Prior to the announcement of the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election, the websites "Okinawa Gubernatorial Election 2018" and "Okinawa Base Problem.com" appeared, but it was unclear whether most of the articles and videos were critical of the Tamaki camp. "Steps taken in Japan to verify fake information aimed at eligible voters in House of Councilors election", Asahi Shimbun, July 6, 2019

13 "'Candidate's denial of involvement in introducing block grants deemed false, created during DPJ administration", Ryukyu Shimpo, September 21, 2018, https://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-805893.html (accessed April 22, 2021)

14 Michael E. Porter, Bruce L. Batten et al.

15 Devin Stewart, "China's Influence in Japan: Everywhere Yet Nowhere in Particular," Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 23, 2020.

16 Ibid.

17 Instituto Affari Internazionali, "EU-Japan Cooperation in Countering Disinformation Campaigns", YouTube, April 15, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fvyG9yX0NUc&t=476s (accessed April 20, 2021).

18 General Secretariat of the Council, "EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific - Council Conclusions (16 April 2021)," Council of the European Union, April 16, 2021, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7914-2021-INIT/en/pdf (accessed April 20, 2021).